Louisiana Commercial Leases Recording La Civ Code Arts 2668 Et Seq

The Law of France refers to the legal organization in the French Republic, which is a civil police force legal organization primarily based on legal codes and statutes, with example law likewise playing an of import role. The most influential of the French legal codes is the Napoleonic Civil Code, which inspired the civil codes of Europe and later on across the earth. The Constitution of France adopted in 1958 is the supreme law in France. European union law is becoming increasingly important in France, every bit in other European union member states.

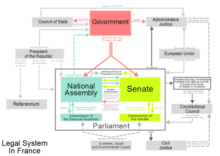

French system of Jurisdiction

In academic terms, French constabulary can be divided into two chief categories: private law (Droit privé) and public law (droit public). This differs from the traditional common constabulary concepts in which the main stardom is between criminal police force and civil law.

Private law governs relationships between individuals.[1] It includes, in particular:[2]

- Ceremonious police force (droit civil ). This branch refers to the field of private law in common police force systems. This branch encompasses the fields of inheritance law, ceremonious law, family constabulary, property law, and contract law.

- Commercial law (droit commercial )

- Employment police (droit du travail )

Public police force defines the structure and the workings of the government as well equally relationships between the state and the individual.[i] It includes, in particular:

- Criminal law (droit pénal )

- Administrative police force (droit administratif )

- Constitutional law (droit constitutionnel )

Together, these two distinctions class the courage of legal studies in France, such that it has become a classical distinction[two]

Sources of Law [edit]

Legislation is seen equally the primary source of French law.[3] Unlike in mutual law jurisdictions, where a collection of cases and practices (known as the "mutual constabulary") historically form the basis of law,[iv] the French legal system emphasizes statutes as the primary source of law.[3] Despite this emphasis, some bodies of police force, like French authoritative law, were primarily created by the courts (the highest authoritative courtroom, the Conseil d'État). [3] Lawyers often look to example law (la jurisprudence) and legal scholarship (la doctrine) for reliable, merely non-binding, interpretation and statements of the law.[v]

Legislative sources [edit]

French legislative sources can be classified into 4 categories:[3]

- Constitutional laws,

- Treaties,

- Parliamentary statutes (loi), and

- Government regulations (règlements).

Hierarchy of norms [edit]

French legislation follows a hierarchy of norms (hiérarchie des normes). Constitutional laws are superior to all other sources, then treaties, then parliamentary statutes (loi),[six] then government regulations.[three] Legislation enacted past orders (ordonnances) and regulations issued by the executive nether Art. 38 of the constitution (Règlements autonomes) accept the aforementioned status as parliamentary statutes.[5]

EU constabulary and international treaties [edit]

European Union treaties and EU law enacted under the dominance of European union treaties are superior to domestic law.[three] [7] French courts consider the French Constitution to be superior to international treaties, including EU treaties and Eu law.[8] This is in contrast to Eu institutions, which sees Eu law every bit superior to the laws of member states.[ix]

Legislation [edit]

There are several categories of legislation:

- Organic statutes (Lois organiques) are laws on areas specified in the Constitution, like presidential elections and the status of judges.[three] Organic statutes must be referred to the Constitutional Quango before they are passed, under Art. 46 of the Constitution.[3]

- Referendum statutes (Lois référendaires) are laws adopted past plebiscite.[3] The President has the power to refer certain bills, on the organisation of public powers, social, economic, and environmental policy or the ratification of a treaty to a referendum, under Art. eleven of the Constitution.[3]

- Orders (ordonnances) are legislative instruments issued by the executive, post-obit Parliament delegation of law-making ability in specific areas.[three] Parliament kickoff delegates law-making ability on an area, along with the full general contours of the law. Orders are then issued by the Council of Ministers, after consultation with the Quango of State (normally a judicial establishment) in its authoritative capacity.[3] Orders are usually valid for 3 to 6 months and need to exist not voted down past Parliament at the end of the menstruation to gain the condition of statutes.[3] [5] Prior to approval they are considered regulations.[three] New codes and major legal reforms are oftentimes enacted past orders.[3]

- Ordinary statutes (Lois ordinaires) enacted by the French Parliament, concerning but matters listed in Art. 34 of the Constitution.[3] These matters include ceremonious liberties, nationality, civil status, taxes, criminal constabulary, and criminal process.[3] However, reverse to the expectations of when the 1958 Constitution was adopted, Parliament has often had a majority supporting the regime.[10] This political reality meant that Parliament'southward legislative domain has been, in practice, expanded to include whatsoever of import topic.[10] Subjects included in Art. 34 cannot be delegated to the government, other than by orders.[3]

- Regulations (règlement) are legislations produced by the executive ability.[iii] There are two types of regulations:

- Règlements autonomes: under Art. 38 of the Constitution, any subject area not expressly specified in Art. 34 is left entirely to the executive.[3] The legislative power is thus shared between the Parliament and the executive.[3] Règlements autonomes have the force of law.[three]

- Règlements d'application are rules arising from parliamentary delegation, analogous to delegated legislation in the United Kingdom.[three] They can be challenged in authoritative courts as reverse to the delegating statute.[iii]

Circulaires [edit]

By dissimilarity, administrative circulaires are not constabulary, merely instructions past authorities ministries.[iii] Circulaires are nonetheless important in guiding public officials and judges.[three] For example, the Circulaire of 14 May 1993 contains detailed instructions for prosecutors and judges on how to apply new rules in the 1992 revised criminal code.[3] Circularies are not considered sources of police in private courts, but are sometimes considered binding in administrative courts.[11] [3] As such, the bounden circulaires règlementaires are reviewed like other administrative acts, and can be constitute illegal if they contravene a parliamentary statute.[12] [3]

Example law [edit]

Case law (la jurisprudence) is non binding and is not an official source of law, although it has been de facto highly influential.[13] 56 [5] French courts have recognized their function in gradually shaping the constabulary through judicial decisions,[14] and the fact that they develop judicial doctrine, especially through jurisprudence constante (a consistent set of example law).[fifteen] At that place is no law prohibiting the citation of precedents and lower courts ofttimes do.[16] Although the highest courts, the Court of Cassation and the Council of State practise not cite precedents in their decisions, previous cases are prominent in arguments of the ministère public and the commissaire du gouvernement, in draft opinions, and in internal files.[5] [17] [eighteen] [19]

Some areas of French law even primarily consist of instance law. For case, tort liability in private law are primarily elaborated past judges, from only five articles (articles 1382–1386) in the Ceremonious Lawmaking.[20] [21] Scholars have suggested that, in these fields of police, French judges are creating police force much like common law judges.[thirteen] 82 [22] Example law is also the main sources for principles in French administrative police force.[19] Many of the Constitutional Council'southward decisions are disquisitional for understanding French constitutional law.[23]

The differences between French case law and case law in common law systems appear to exist: (i) they are non cited in the highest courts;[5] [17] [18] [nineteen] (2) lower courts are theoretically free to depart from higher courts, although they risk their decisions being overturned;[5] and (3) courts must not solely cite case law as a basis of decision in the absence of a recognized source of law.[24] [5]

French judicial decisions, especially in its highest courts, are written in a highly laconic and formalist style, being incomprehensible to non-lawyers.[25] [26] While judges do consider practical implications and policy debates, they are not at all reflected in the written decision.[27] This has led scholars to criticize the courts for being overly formalistic and even disingenuous, for maintaining the facade of judges only interpreting legal rules and arriving at deductive results.[5]

Codes [edit]

Following the case of the Napoleonic Civil Code, French legal codes aim to set out authoritatively and logically the principles and rules in an area of law.[28] In theory, codes should become beyond the compilation of discrete statues, and instead state the constabulary in a coherent and comprehensive piece of legislation, sometimes introducing major reforms or starting anew.[28]

There are about 78 legal codes in French republic currently in force, which deal with both the French public and private law categorically. These codes are published for gratis past the French government on a website called Legifrance.[29]

In 1989, the French government fix the Commission Supérieure de Codification, tasked with codifying laws.[28] The Commission has worked with ministries to introduce new codes and formulate existing legislation.[28] Unlike the transformative Civil Code under Napoleon,[5] the goal of the modern codification project is to clarify and make more than accessible statutes in by compiling ane code in a detail expanse of police and remove contradictions.[28] Despite this, areas very often overlap and codes necessarily cannot incorporate all of the law in a given field.[28]

History [edit]

In the High Middle Ages, most legal situations in France were highly local, regulated by customs and practices in local communities.[30] Historians tend to exist attracted by the big regional or urban customs, rather than local judicial norms and practices.[30] Beginning in the 12th century, Roman law emerged as a scholarly subject field, initially with professors from Bologna starting to teach the Justinian Code in southern France[31] and in Paris.[32] Despite this, Roman law was largely academic and disconnected from application, especially in the n.[32]

Historians traditionally mark a distinction between Pays de droit écrit in southern France and the Pays de droit coutumier in the north.[32] In the southward, it was thought that Roman law had survived, whereas in the northward it had been displaced past customs afterwards the Germanic conquest.[32] Historians now tend to recollect that Roman police was more influential on the customs of southern French republic due to its medieval revival.[32] Past the 13th century, at that place would be explicit recognition of using Roman law in the south of France, justified by the agreement of a longstanding tradition of using Roman law in the custom of southern France.[33] [32] In the North, individual and unofficial compilations of local customs in different regions began to emerge in the 13th and 14th centuries.[32] These compilations were often drafted by judges who needed to determine cases based on unwritten customs, and the authors often incorporated Roman police, procedures from canon constabulary, royal legislation and parliamentary decisions.[32]

In the early on mod period, laws in France gradually went through unification, rationalization, and centralization.[32] Later on the Hundred Years War, French kings began to assert authority over the kingdom in a quest of institutional centralization.[32] Through the creation of a centralized accented monarchy, an administrative and judicial system under the king also emerged by the 2d half of the fifteenth century.[32] Majestic legislation likewise greatly increased beginning in the 15th century.[32]

The Ordinance of Montils-les-Tours (1454) was an of import juncture in this period, as it ordered the official recording and homologation of customary police.[32] Customs would be compiled by local practitioners and approved by local assemblies of the three estates, with disagreements resolved past the central court.[32] At the time, the wholesale adoption of Roman constabulary and the ius commune would be unrealistic, as the king's authority was insufficient to impose a unified legal system in all French provinces.[32] In the process of recording, local customs were sometimes simplified or reformed.[32] By the 16th century, effectually sixty general customs were recorded and given official status, disqualifying any unrecorded customs from having official status.[32] Roman law remained as a reserve, to be used for argumentation and to supplement customary law.[32]

Accompanying the process of centralization and mercantilism, the king effectively initiated processes of codification in the mid 17th century.[32] [34] Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Minister of Finance and afterwards also Secretary of the Navy in charge of the colonial empire and trade, was main architect of the codes.[32] The commencement of such codes is the 1667 Ordinance of Civil Procedure (officially known every bit the Ordonnance cascade la reformation de la justice), which established clear and uniform procedural rules, replacing previous rules in all purple jurisdictions and in the colonies.[35] [32] The 1667 Ordinance is the chief inspiration of the Code de procedure civile passed in 1806 nether Napoleon.[32] Other codes include the 1670 Criminal Ordinance, the 1673 Ordinance for Overland Merchandise (Code Marchand), and the 1681 Ordinance for Maritime Trade (Code de la Marine).[32] Ordinances would afterward exist drawn upwards on Donations (1731), Wills (1735), Falsifications (1737), and Trustees (1747), but a unified code of private police would non exist passed until 1804, nether Napoleon and later on the French Revolution.[32] Under Male monarch Louis Fifteen,[36] there would be a constant struggle between regal legislation, traditional conceptions of the law of the Realm (customs and Roman constabulary), and parliamentary arrêts de règlements (regulatory decisions).[37] [32] Judges sided with the local parliaments (judicial bodies in French republic) and the landed aristocracy, undermining majestic authority and legislation.[38] [39]

Fifty-fifty before the French Revolution, French enlightenment thinkings like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with a theory of natural rights, and especially Montesquieu, who advocated for a separation of powers were major influences on the constabulary throughout Europe and the U.s.a..[40] [32]

The French legal system underwent great changes after the French Revolution beginning in 1789, which swept away the onetime regime.[32] By 1790, the National Constituent Assembly overhauled the land'south judicial arrangement.[32] A criminal code would exist adopted by 1791. The Civil Lawmaking (1804), the Code of Civil Procedure (1806), and the Commercial Code (1807) were adopted under Napoleon Bonaparte, reflecting Roman law, pre-revolutionary ordinances and custom, scholarly legal writings, enlightenment ideas, and Napoleon'due south personal vision of the constabulary.[32] These codes consisted of numbered articles, were written in elegant French, and were meant to be understood past the layman.[28] [5] In addition, they introduced many classically liberal reforms, such as abolishing remaining feudal institutions and establishing rights of personality, property and contract for all male person French citizens.[41]

Private law [edit]

The term civil constabulary in France refers to private police (laws between private citizens, and should be distinguished from the group of legal systems descended from Roman Law known every bit civil law, every bit opposed to common constabulary.

The major private law codes include:

- The Civil Code,

- The Code of Civil Procedure,

- The Commercial Code, and

- The Intellectual Property Code.

Civil process [edit]

France follows an inquisitorial model, where the judge leads the proceedings and the gathering of show, acting in the public interest to bring out the truth of a case.[42] This is contrasted with the adversarial model frequently seen in common law countries, where parties in the case play a main part in the judicial process.[42] In French civil cases, ane party has the burden of proof, according to law, simply both sides and the judge together get together and provide evidence.[42] In that location is no strict standard of proof in civil cases, like the preponderance of the evidence under American law; instead, primacy is given to the judge'south intime conviction,[42] based on the principle of "gratis evaluation of the testify."[43]

The courtroom gathers a dossier of pleadings, statements of fact and testify from the parties and makes it bachelor to them. [42] [44] Proceedings focus on written evidence and written argument, with brief hearings. [42] Witness testimonies are uncommon. [42] The ministère public, an contained judicial official, sometimes plays an advisory role in civil proceedings. [42] In principle, the showtime level of appellate court reviews questions of both fact and police, and it is able to do so because of the dossier. [42] It can too guild additional investigations and product of prove. [42] [45] The Court of Cassation (highest civil appellate court) generally just decides questions of law and remands the example for further proceedings. [42]

Public law [edit]

Public law is concerned with the powers and organisation of the state and governmental bodies.[46]

Constitutional law [edit]

French ramble law includes non simply the Constitution itself, but also its preamble which incorporates a list of norms known as bloc de constitutionnalité, including:[47]

- Rights listed in the 1789 Annunciation of the Rights of Man and of the Denizen: including classical liberal rights on private freedom, correct to belongings and contract, and equality.[47] [v]

- Social and economical rights listed in the preamble to the old 1946 Constitution: including the rights to health, education, trade union activity, and work.[47] [5]

- Fundamental principles recognized by the laws of the Commonwealth: in theory this composes of freedoms and liberties recognized by legislation in the Third Republic, although courts have taken some freedom to expand such principles.[47] [v] [48]

- Rights in the 2004 Lease for the Environment: including abstract principles such equally the principle of sustainable development.[47] [5]

The Constitutional Council (Conseil Constitutionnel) has the exclusive dominance to judge the constitutionality of parliamentary statutes.[three] Although originally conceived as a political body, information technology is now seen much similar a judicial one.[49] The President, Prime Minister, the presidents of both houses of Parliament, and a group of sixty members from either of the 2 houses may refer bills or treaties to the Constitutional Council.[3] In add-on, when individuals allege that their constitutional rights are infringed by legislation in a courtroom proceeding, the Court of Cassation or the Council of Land may refer the matter to the Constitutional Quango for a ruling on its constitutionality.[3]

Administrative law [edit]

In France, well-nigh claims against local or national governments are handled by the authoritative courts, for which the Conseil d'État (Quango of State) is a court of concluding resort. The main administrative courts are the tribunaux administratifs and their entreatment courts. The French trunk of administrative law is chosen droit administratif. Administrative procedure were originally developed by case police but take been statutorily affirmed in the Code de justice administrative in 2000.[42]

French administrative police force focuses on proper operation of government and the public good, rather than constraining the government.[50] French public bodies include governments and public organizations or enterprises, subject to different sets of rules, with both privileges and boosted limitations compared to private actors.[l] Public bodies take tremendous powers, including police powers (pouvoirs de law) to regulate public health or public social club, and to expropriate property.[fifty] Public bodies must exercise their powers in the public interest, co-ordinate to principles such every bit continuity of services (which has been used to limit the power to strike), adjustability (irresolute in accordance with external circumstances), equality and neutrality (in relation to, e.1000. i'southward organized religion or political beliefs).[50] [51]

All acts must have a legal basis (base légale), follow the right process (sometimes including right to a hearing), and washed with a purpose to further public involvement.[50] The court likewise reviews facts (including subjective judgments based on facts, similar the architectural value of a building),[52] and interpret the law.[50] There are also three levels of scrutiny, namely:

- maximum control (define both the correctness of the facts and the ceremoniousness of the evaluation),[50]

- normal control (ensuring that the facts are sufficient to justify the conclusion and that the constabulary had been interpreted correctly),[l] and

- minimum command (only interfere where the assistants has apparently exceeded its powers, including manifest error in evaluation and disproportionate decisions).[50]

Recourses provided by the court include amercement, setting aside contracts, amending contracts, quashing an authoritative determination, or interpret the law (only available to the Council of Land, although lower courts may refer questions to it).[42] Different procedures exist depending on the recourse sought.[42] Injunctions are rare but can be issued in sure procedures (référés).

Certain acts past the French government, called acte de gouvernement, avoids judicial review as they are too politically sensitive and beyond judicial expertise.[53] [54] Such acts include the President to launch nuclear tests, sever fiscal aid to Iraq, dissolve Parliament, honor honors, or to grant amnesty.[54] Other nonjusticiable acts include sure internal diplomacy of government ministries (Mesures d'ordre interne), e.chiliad. the decision to alter the frequency of services, unless doing so is confronting the police force.[fifty]

Administrative procedure [edit]

Before judicial recourse, 1 may request authoritative appeals (recours préalable) by the official or his superior, although they are of limited use.[42] Legal aid is available similar in civil and criminal cases, although lawyers are unnecessary in many cases because under the French inquisitorial legal arrangement, judges accept principal control of cases afterward their introduction.[42] All administrative decisions must exist challenged within 2 months of their being taken and no waiver is possible for lapses.[42]

To begin a case, an private just need to write a letter to describe his identity, the grounds of challenging the decision, and the relief sought, and provide a copy of the administrative activity; legal arguments are unnecessary in the initial stage.[42] A court rapporteur will assemble data (he has the ability to request documents from the public trunk), compile written arguments from both sides, and request proficient assessments if necessary.[42] The files and the rapporteur's recommendations are transferred to a Commissaire du gouvernement, who as well makes his own recommendations to the judges.[42] Written show is relied upon and oral hearings are extremely short.[42] Afterward the hearing, judges deliberate and consequence their sentence, in which they volition briefly answer to parties' arguments.[42]

Standing requirements in French authoritative law are relatively lax.[42] Although merely existence a taxpayer is insufficient, those affected in a "special, certain and directly" manner (including moral interests) will have standing.[42] In addition, users of public service can generally claiming decisions on those services.[42] Associations can also have standing in some circumstances.[42]

Criminal constabulary [edit]

French criminal law is governed first and foremost past the Criminal Lawmaking and the Code of Criminal Procedure. The Criminal Code, for example, prohibits violent offenses such as homicide, assault and many pecuniary offenses such as theft or money laundering, and provides general sentencing guidelines. However, a number of criminal offenses, e.thousand., slander and libel, have not been codified but are instead addressed by separate statutes.[55]

Criminal procedure [edit]

After a criminal offence occurs, the police make initial investigations.[42] The prosecutor (procureur) or, in some serious cases, the juge d'teaching so control or supervise the police investigation and decide whether to prosecute.[42] Unlike common law countries and many civil police force countries, French prosecutors are members of the judicial branch.[42] Issuing arrest warrants or formally questioning the accused or witnesses must receive judicial blessing,[56] but decisions on searches and phone-tapping are oft delegated to the police force because of limited judicial resources.[42] There are also simplified procedures for crimes in flagrante delicto and crimes relating to terrorism and drugs.[42]

Other judges then preside at the criminal trial, typically without a jury. All the same, the almost serious cases tried by the cour d'assises (a branch of the Court of Appeal) involve iii judges and nine jurors who jointly determine the verdict and sentencing.[42] Similar civil proceedings, criminal proceedings focus on written evidence and written statement, although witnesses are unremarkably as well heard orally.[42] Judges or prosecutors order independent experts for the proceeding, if necessary.[42] One entreatment can be made on questions of fact and law, save for decisions of the cour d'assises.[42] Appeals may also be made to the Courtroom of Cassation on questions of law.[42] Other judges (the juge de fifty'awarding des peines) supervise the sentence and bargain with parole.[42]

European Union Police [edit]

The French Constitution specifically authorizes France'due south participation in the Eu (Eu), an economic and political union with many legal powers.[57] The Constitution has likewise been amended, as required by the Constitutional Council,[58] to allow European union citizens to participate in municipal elections and the monetary union.[5] EU treaties and Eu law enacted under the treaties are considered international treaties, and the Constitution gives them superior status compared to domestic legislation.[iii] [7] Ordinary civil and administrative courts, non the Constitutional Council, determine the compatibility of French police with European union law.[5]

French courts consider the French Constitution itself to be superior to international treaties, including Eu treaties and EU constabulary.[viii] This is in contrast to European union institutions, which sees Eu constabulary as superior to the laws of member states.[9] All the same, the Constitutional Council would just examine statutes implementing Eu directives where information technology was patently reverse to French constitutional principles.[59]

The European Spousal relationship adopts laws on the basis of European union treaties. The Treaties constitute the EU's institutions, list their powers and responsibilities, and explain the areas in which the EU can legislate with Directives or Regulations. European Marriage laws are a torso of rules which are transposed either automatically (in the case of a regulation) or past national legislation (in the example of a directive) into French domestic law, whether in civil, criminal, administrative or ramble law. The Courtroom of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is the principal judicial body of EU laws. The EU'due south view is that if EU law conflicts with a provision of national constabulary, so European union law has primacy; the view has been gradually accepted by French courts.[3]

Judicial institutions [edit]

French judicial arrangement [edit]

French courts get past a number of names, including juridiction, tribunal, and cour. [46] The Constitutional Council and Council of State are nominally councils but de facto courts.[46] French courts are often specialized, with split public police and private police force courts, and subject matter specific courts like general civil and criminal courts, employment, commercial and agricultural lease courts.[46] Judges are typically professional civil servants, by and large recruited through exams and trained at the École Nationale de la Magistrature. [sixty] There are also non-professional judges, typically in less serious civil or authoritative cases.[46]

In public constabulary cases, a public trunk, such as the national authorities, local authorities, public agencies, and public services similar universities to railways, are always a party in dispute.[46] Public bodies are subject to different rules on their ability, contract, employment and liabilities.[46] Instead of rules in the Civil Code and Commercial Code, administrative law statutes and principles developed by the Quango of State are applied.[46] Individual law disputes between individuals or private entities are heard in civil courts.[46] The Tribunal des conflits resolves questions of appropriate court jurisdiction.[46]

Administrative law courts [edit]

The Council of Land (Conseil d'État) is the highest court in authoritative law and also the legal counselor of the executive branch.[3] Information technology originated from the Male monarch's Privy Quango, which adjudicated disputes with the state, which is exempt from other courts considering of sovereign amnesty.[46] The Council of Country hears appeals on questions of police from lower courts and gives informational opinions on the police on reference from lower courts.[46] Information technology also decides at starting time instance the validity of legislative or authoritative decisions of the President, the Prime Government minister, and certain senior civil servants.[46]

There are 42 lower administrative courts and 8 authoritative courts of entreatment, which hears appeals on fact and police force.[3] Administrative courts tin enforce their decisions by ordonnance to the public body.[46] In addition to generalist administrative courts, there are special authoritative courts on aviary, social welfare payments, the disciplinary organs of professional person bodies, and courts that audit public bodies and local governments.[46] Administrative court judges are selected separately from other judges.[46]

Civil and criminal courts [edit]

The Court of Cassation (Cour de Cassation) is the highest court and the merely national court on civil and criminal matters.[3] Information technology has six chambers, five civil chambers: (i) on contract, (ii) on delict, (three) on family matters, (iv) on commercial matters, (five) on social matters: labour and social security constabulary; and (vi) on criminal law.[46] The court has 85 conseillers, 39 junior conseillers réferendaires, and 18 trainee auditeurs.[46] It typically hears cases in iii or five judge panels. A chambre mixte (a large panel of senior judges) or plenary session (Assemblée plénière) can convoke to resolve conflicts or hear important cases.[46] In 2005, it decided over 26,000 cases.[46] The Court of Cassation also gives advisory opinions on the law on reference from lower courts.[46]

At the appellate level, there are 36 Courts of Appeal (cour d'appel), with jurisdiction on appeals in civil and criminal matters.[3] A Courtroom of Appeal volition usually have specialist chambers on civil, social, criminal, and juvenile matters.[46] The cour d'appel deals with questions of fact and police force based on files from lower courts, and has the power to order additional investigations.[46]

As for courts of kickoff instance, there are 164 tribunaux de grande instance (ceremonious courts for big claims, family unit matters, nationality, belongings and patents)[46] and 307 tribunaux d'instance (civil courts for medium-sized claims).[3] Divide commercial courts bargain with commercial matters at the first instance, with lay judges elected by the local chamber of commerce.[46] For criminal matters, the tribunal de law, the juges de proximité, the tribunal correctionnel and the cour d'assises hear criminal cases, depending on their seriousness.[46] The cour d'assises is a branch of the Court of Appeal, which hears at offset instance the most serious criminal cases.[46] In criminal trials heard by the cour d'assises, three judges and nine jurors together determine the verdict and sentencing.[46] Criminal and civil courts are connected and typically co-located, despite criminal law existence a branch of public law.[46]

Constitutional Council [edit]

The Constitutional Council (Conseil Constitutionnel) was created in 1958 with sectional authorisation to guess the constitutionality of parliamentary statutes.[three] The President may refer a beak in Parliament to the Ramble Council for constitutional review.[iii] The Prime Minister, the presidents of both houses of Parliament, and a grouping of 60 members from either of the 2 houses may as well refer bills or treaties to the Constitutional Council.[3] In addition, under Art. 61–1 of the Constitution, beginning in 2008, when individuals allege that their constitutional rights are infringed by legislation in a court proceeding, the Court of Cassation or the Council of State may refer the affair to the Constitutional Council for a preliminary ruling on its constitutionality.[3] The Constitutional Council has nine members: three are appointed by the President, iii by the head of the National Assembly, and iii by the head of the Senate.[61] Members of the Constitutional Council do not necessarily have legal or judicial training; former French Presidents who retired from politics are eligible to join the Constitutional Council if they wish.[46]

Meet as well [edit]

- Legal systems of the world

- 1825 Anti-Sacrilege Human activity

- Jules Ferry laws

- Lois scélérates

- La regle de not-cumul, which regulates action under contract law versus tort police

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Cornu, Gérard (2014). Vocabulaire Juridique (in French) (10 ed.). Paris: PUF.

- ^ a b Terré, François (2009). Introduction générale au droit. Précis (in French) (8 ed.). Paris: Dalloz. pp. 91–95.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k fifty m n o p q r south t u 5 west x y z aa ab air conditioning advertizement ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Steiner, Eva (2018-04-19). Legislation and the Constitutional Framework. Vol. i. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790884.003.0001. ISBN978-0-19-183334-2.

- ^ Merryman, J. H., and Perez-perdomo, R., The Ceremonious Law Tradition, Stanford: Stanford Academy Printing, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f k h i j k l m n o p q Bell, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008). "Sources of law". Principles of French Police. Oxford Academy Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.003.0002. ISBN978-0-19-954139-iii.

- ^ Commodity 55 of the French Constitution, which states: "Treaties or agreements duly ratified or approved shall, upon publication, prevail over Acts of Parliament, subject field, with respect to each agreement or treaty, to its application by the other party."

- ^ a b Meet Art. 88-1 of the Constitution, laying down the Eu institutional and legal framework

- ^ a b See Conseil d'État, ruling in Sarran, Levacher et autres (1998), AJDA, 1039. See too the Court of Cassation conclusion in Pauline Fraisse (2000), Balderdash. ass. plen., no 4.

- ^ a b Costa 5 ENEL [1964] ECR 585

- ^ a b Colloque Aix-en-Provence, Vingt ans d'application de la Constitution de 1958: le domaine de la loi et du règlement (Marseille, 1988)

- ^ Conseil d'État in Institution Notre Dame du Kreisker (1954), RPDA, fifty

- ^ See, e.thou. Syndicat des producteurs indépendants (1997), D. 1997, 467

- ^ a b F.H. Lawson, A Common Lawyer looks at the Civil Police (Ann Arbor, 1953)

- ^ Run across, e.g. Cour de cassation, Rapport annuel 1975 (Paris, 1976), 101

- ^ Fifty'prototype doctrinale de la Cour de cassation (Paris, 1994)

- ^ R. David, French Constabulary (Billy Rouge, 1972) 182-183

- ^ a b J. Bell, 'Reflections on the process of the Conseil d'Etat' in Grand. Hand and J. McBride, Droit sans frontières (Birmingham, 1991)

- ^ a b M Lasser, 'Judicial (Self-)Portraits: Judicial Soapbox in the French Legal System' (1995) 104 Yale LJ 1325

- ^ a b c J. Bong, French Legal Cultures (Cambridge, 2001) 175–185.

- ^ Les conditions de la responsabilité 3rd edn. (Paris, 2006)

- ^ Les effets de la responsabilité 2nd edn. (Paris, 2001)

- ^ K. Ripert, Le régime démocratique et le droit ceremonious moderne, vol. 2 (Paris, 1948), 15

- ^ See G. Vedel, 'Le précédent judiciaire en droit public', in Die Bedeutung von Präjudizien in deutschen und französischen Recht (Arbeiten zur Rechtsvergleichung no. 123 (Frankfurt/Main, 1985).

- ^ E.g. Crim. 3 November. 1955, D 1956.557 note Savatier, where a Cour d'appel's decision was quashed because information technology had refused to exceed its normal maximum level of damages.

- ^ A. Perdriau, La pratique des arrêts civils de la Cour de cassation: principes et méthodes de rédaction (Paris, 1993)

- ^ B. Ducamin, 'Le style des décisions du Conseil d'Etat' EDCE 1984–1985.129

- ^ M. Lasser, Judicial Deliberations. A Comparative Analysis of Judicial Transparency and Legitimacy (Oxford, 2004), xvi, 44–61

- ^ a b c d e f g Steiner, Eva (2018). "Codification". French Constabulary. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198790884.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-879088-4.

- ^ "Légifrance".

- ^ a b Hespanha, António (2018-08-08). Pihlajamäki, Heikki; Dubber, Markus D.; Godfrey, Marker (eds.). Southern Europe (Italy, Iberian Peninsula, France). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198785521.013.17. ISBN978-0-19-878552-ane.

- ^ André Gouron, La Science du droit dans le Midi de la France au Moyen Âge (Variorum 1984)

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u five w 10 y z aa ab ac Dauchy, Serge (2018-08-08). Pihlajamäki, Heikki; Dubber, Markus D.; Godfrey, Mark (eds.). French Police and its Expansion in the Early Modern Period. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198785521.013.32. ISBN978-0-19-878552-1.

- ^ Jean Bart, Histoire du droit privé: de la chute de l'Empire romain au XIXe siècle (Montchrestien 1998) 112-fourteen.

- ^ Jean-Louis Halpérin, Five Legal Revolutions since the 17th Century: An Assay of a Global Legal History (Springer 2014) 35 ff

- ^ Van Caenegem, 'History of European Civil Procedure' (north ii) 45 ff.

- ^ Serge Dauchy, 'Séance royale du iii mars 1766 devant le Parlement de Paris dit séance de la Flagellation' in Julie Benetti, Pierre Egéa, Xavier Magnon, and Wanda Mastor (eds), Les Grands discours juridiques, Dalloz, drove les grands arrêts, 2017.

- ^ Philippe Payen, Les Arrêts de règlement du Parlement de Paris au XVIIIe siècle (Presses universitaires de France 1997).

- ^ Alexis de Tocqueville, The Quondam Government and the French Revolution

- ^ Georges Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution 17-18 (Palmer, tr. 1967)

- ^ Stella Ghervas, 'The Reception of The Spirit of Law in Russia: A History of Ambiguities' in Michel Porret and Catherine Volpilhac-Auger (eds.), Le Temps de Montesquieu (Droz 2002) 391–403.

- ^ John Henry Merryman, The French Divergence, The American Periodical of Comparative Law, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Winter, 1996), pp. 109- 119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j thou l k northward o p q r s t u v due west x y z aa ab ac advert ae af ag ah ai aj ak Bong, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008-03-27). "Legal Procedure". Principles of French Police. Oxford University Printing. doi:x.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.003.0005. ISBN978-0-xix-954139-3.

- ^ "Evidence - Relevance and admissibility". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2020-05-29 .

- ^ Arts. 14 and xv North.c.pr.civ. E.g. Ch. mixte 3 February. 2006, Droit et procédure 2006.214 (absence of advice of documents in suitable time (temps utile)).

- ^ Art. 563 N.c.pr.civ.

- ^ a b c d east f g h i j yard l thousand northward o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Bell, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008). "Courtroom Institutions". Principles of French Law. Oxford University Printing. doi:ten.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.003.0003. ISBN978-0-19-954139-iii.

- ^ a b c d e Run across Conseil Constitutionnel Decision 71–44 DC, 16 July 1971, Liberté d'association, Rec. 29

- ^ J. Bell, French Constitutional Law (Oxford, 1992), 70–71

- ^ Bong, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008-03-27). "Constitutional Law". Principles of French Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-954139-3.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j Bell, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008-03-27). "Administrative Law". Principles of French Law. Oxford University Printing. doi:x.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-954139-3.

- ^ Meschariakoff, Services publics, 21, 133-35, 176-77

- ^ Gomel, CE 4 Apr 1914, Southward 1917.3.25 note Hauriou.

- ^ Jully, A. (2019). Propos orthodoxes sur fifty'acte de gouvernement: (Note sous Conseil d'Etat, 17 avr. 2019, Société SADE, northward°418679, Inédit au Lebon). Civitas Europa, 43(2), 165-171. doi:10.3917/civit.043.0165.

- ^ a b Bell, John; Boyron, Sophie; Whittaker, Simon (2008-03-27). Principles of French Constabulary. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199541393.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-954139-3.

- ^ Link to Penal Code

- ^ Art. 152 al. 2, C.pr.pén.

- ^ Art. 88-1 et seq. of the Constitution

- ^ C. cons. 9 April 1992, Maastricht Treaty, Rec. 55.

- ^ C. cons. 10 June 2004, Rec. 101.

- ^ Steiner, Eva (2018-04-nineteen). "Judges". French Law. Vol. 1. Oxford Academy Press. doi:ten.1093/oso/9780198790884.001.0001. ISBN978-0-19-879088-four.

- ^ Shaw, Mabel. "Guides: French Legal Research Guide: The Layout of the French Legal Organisation". guides.ll.georgetown.edu . Retrieved 2020-05-28 .

Sources [edit]

- Clavier, Sophie G. (July 1997). "Perspectives on French Criminal Law". San Francisco Country University. Archived from the original (DOC) on 2005-10-31. Retrieved 2008-05-07 .

Farther reading [edit]

- in English

- Bong, John. Principles of French police force. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-nineteen-876394-8, ISBN 0-19-876395-6.

- Bermann, George A. & Étienne Picard, eds. Introduction to French Law. Wolters Kluwer, 2008.

- Cairns, Walter. Introduction to French law. London: Cavendish, 1995. ISBN ane-85941-112-half dozen.

- Dadomo, Christian. The French legal organisation, second edn. London: Sweet & Maxwell, 1996. ISBN 0-421-53970-4.

- David, René. French Law: Its Structure, Sources and Methodology. Trans. Michael Kindred. Billy Rouge, LA: Louisiana State Academy, 1972.

- David, René. Major legal systems in the globe today: an introduction to the comparative study of law, 3rd edn. London: Stevens, 1985. ISBN 0-420-47340-8, ISBN 0-420-47350-5; Birmingham, AL: Gryphon Editions, 1988. ISBN 0-420-47340-8.

- Elliott, Catherine. French legal system. Harlow, England: Longman, 2000. ISBN 0-582-32747-4.

- Reynolds, Thomas. Foreign law: current sources of codes and basic legislation in jurisdictions of the earth. Littleton, Colo.: F.B. Rothman, 1989- . 5. (loose-leaf); 24 cm.; Series: AALL publications series 33; Contents five. ane. The Western hemisphere—five. ii. Western and Eastern Europe—v. 3. Africa, Asia and Australia. ISBN 0-8377-0134-1; http://world wide web.foreignlawguide.com/

- For both an overview and pointers toward further written report, run into the fantabulous introduction to the "France" section

- West, Andrew. The French legal system, 2nd edn. London: Butterworths, 1998. ISBN 0-406-90323-9.

- in French

- Aubert, Jean-Luc. Introduction au droit (Presses Universitaires de France, 2002) ISBN 2-13-053181-4, 127 pages (many editions)

- One of the 'Que sais-je?' series of "pocketbook" volumes, which provide readable short summaries

- Bart, Jean. Histoire du droit (Paris: Dalloz, c1999) ISBN 2-247-03738-0.

- Brissaud, Jean. A history of French public police force (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1915) Serial: The Continental legal history serial five. 9; Note: A translation of pt. Ii (omitting the start two sections of the introduction) of the author'south Manuel d'histoire du droit français .

- French legal history appears throughout near of the above.

- Brissaud, Jean. A history of French private constabulary (Boston: Lilliputian, Chocolate-brown, and Company, 1912) Series: The Continental legal history series five. three. Note: Translation of pt. Three (with the addition of one chapter from pt. 2) of the writer'southward Manuel d'histoire du droit français .

- Brissaud, Jean, 1854-1904. Manuel d'histoire du droit français (Paris: Albert Fontemoing, 1908).

- the original French text

- Carbasse, Jean-Marie. Introduction historique au droit 2. éd. corr. (Paris: Presses universitaires de French republic, 1999, c1998) ISBN 2-xiii-049621-0.

- Castaldo, André. Introduction historique au droit two. éd. (Paris: Dalloz, c2003) ISBN 2-247-05159-6.

- Rigaudière, Albert. Introduction historique à l'étude du droit et des institutions (Paris: Economica, 2001) ISBN two-7178-4328-0.

- Starck, Boris. Introduction au droit 5. éd. (Paris: Litec, c2000) ISBN 2-7111-3221-8.

- Thireau, Jean-Louis. Introduction historique au droit (Paris: Flammarion, c2001) ISBN two-08-083014-7.

External links [edit]

- History of the laws of French republic

- Legifrance:Codes and Texts - a clear and easily followed outline of the French legal construction

- About Law - recommended for beginners

- (in French) Lex Motorcar - French legal news

- (in French) Droit français - a clear and easily followed outline of the French legal structure

- (in French) French site of collective agreements

- (in French) Directory of French law firms

milliganlighervaing.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_in_France

0 Response to "Louisiana Commercial Leases Recording La Civ Code Arts 2668 Et Seq"

Post a Comment